It’s summertime, which means hot dogs and hamburgers are flying off the store shelves, and you can thank F.R. Drake Company—that holds the majority of the market share for frankfurter and cylindrical food loaders—for keeping up with the demand.

F.R. Drake Company’s journey to major global market share started in 1979, when Fredrick R. Drake took his wealth of machine design knowledge, and created the company. A couple of years after the OEM’s inception, Drake went to market with a new frankfurter loading system that was 25 percent faster than the leading loader at the time.

The new design and fast throughput launched Drake into the commercial food equipment business. Over the next 20 years, the family-owned OEM grew steadily, introduced product innovations and became the Western Hemisphere market leader. That caught the attention of private equity firm Fullham & Co., which acquired Drake in 2005. From there, Drake boldly went into acquisition mode to expand its product line, as well as to solidify its foothold in the global market. In 2011, Drake was acquired once again by Middleby’s Food Processing group.

In a world where mergers and acquisitions can cause the collapse of a company, Drake is an example of how a small OEM can effectively navigate the acquisition maze to create global market growth and a broader product portfolio. The company is also rooted in research and development and is not afraid to take a technology risk—even if means building their own robot—which they did. But people drive success, which is why Drake has implemented strategies that leverage home grown talent in its effort to build a lasting legacy.

Adapting to rapid growth

When Drake began acquiring companies like Planet Products, the OEM doubled the size of its business overnight. The company was used to only processing one loader at a time, but they were suddenly faced with having multiple assemblies in the shop at once. To meet the change in production, the company incorporated “Gemba walks,” a lean manufacturing technique that stands for “understanding a current process as-is before taking any action to improve that process.” An increasingly popular management technique, Gemba walks provide insight into the flow of work by talking with employees, thereby uncovering areas of improvement.

“Prior to the acquisition, we didn’t even realize how much tribal knowledge had been developed,” says George Reed, Drake’s vice president of engineering and operations. “We had a high-level of familiarity with how our equipment was assembled, so we were able to operate independently of any type of business process management software. But when we brought in all of this new equipment that our engineers had never seen before, it quickly became apparent that we didn’t have adequate systems to track our progress on assemblies in place.”

In an effort to solve system disconnect, the OEM installed whiteboards throughout its facility, both in the office area and on the plant floor, to track the progress of all projects. Employees write their goals and share the status of the projects they are assigned to on these whiteboards, and then, during the Gemba walk, the management team checks in on these projects and resolves any issues that may arise during assembly.

To accommodate incoming, younger generations, Ivy implemented a high-tech route to Gemba by installing a touch screen TV in the front office to get real-time updates. Employees can also track these updates on their mobile devices through Rhythm Systems, cloud-based coaching and business execution software that helps companies predict growth results by keeping people accountable.

The Gemba techniques drive common priorities and cooperation between all of the OEM’s different departments so that they can continue to grow while staying on track with current projects and objectives, Reed says.

Automation elevates product offering

One of the bigger objectives at Drake is to expand its market footprint in the autoloading of food products outside of just cylindrical shaped products like hot dogs and sausages. The company’s acquisition model has helped immensely by adding new product lines and capabilities to the OEM’s portfolio.

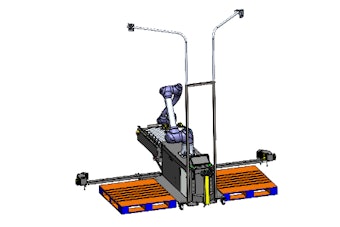

For example, when Ivy joined the company in 2012, all of the OEM’s equipment had mechanical loading heads, but the industry shifted and customers began demanding smaller, more versatile pieces of automated equipment. Ivy understood the potential for automation in food processing, especially given the growth trajectory. According to a 2017 PMMI Business Intelligence Report on the evolution of automation, automated applications in the packaging and processing space will grow 100 percent within the next 10 years. This shift, and the need for equipment that handled different product sizes and shapes, prompted Drake to develop robotic loaders as a FANUC integrator in 2014.

“Robotics opens up the market to our smaller customers,” Ivy says. “The technology really allows us to make headway into that market because of the versatility. These companies have one machine, and they will load big sausages and little sausages in different directions, and that may vary on a daily basis. And when you’re loading everything mechanically, you can’t do all of that. Whereas with a robot, you can.”

These robotic loaders now make up 50 percent of the OEM’s business. In addition, as Drake began to sell into markets that needed robotic food processing solutions, the company noticed a gap in the marketplace for hygienic robotic loaders. That’s when Drake decided to develop its own PLC-controlled, stainless steel and titanium robot. To make the robot even more flexible, the OEM is creating its own programming and kinematics for it, which will allow it to communicate with other portions of the packaging line more efficiently.

“In a traditional robotic system, it would use vision to confirm the position of the incoming products, whereas, now, we can use our sorting system and convey that information directly into the program,” Reed says. “This means the robot can start moving into position because we know where the product is, we don’t have to use a vision system to find it.”

Product innovations launch Drake into new markets

Along with building its own robot, Drake always has its sights set on new markets, even if that means the hot dog loading equipment manufacturer crosses over into the other side of protein processing—hamburgers.

It’s most recent project is automating the loading of fresh hamburgers into the oven broiler of one of its Middleby sister companies. And the OEM has also started working with a casual dining company on a similar process.

“We’ve got every potential loading option for every kind of sausage,” Ivy says. “The next viable market for us is really any kind of protein to continue to grow and expand our market footprint.”

A major selling point that Ivy uses when breaking into these new markets is reducing labor, because the cost and availability of labor is a common pain point among food processers.

“It’s only a dollar an hour in the Philippines to pay somebody to run a mechanical processing line, but it’s hard to find people to do that, or the operators simply don’t show up,” Ivy says. “On the other hand, in Australia, it costs $60 an hour to have someone operate equipment at a meat plant.”

Another factor playing into the labor pain point is the strict sanitation regulations that food processors have to abide by.

“Every time someone walks into a food plant, they bring dozens of new microflora with them,” Ivy says. “So the fewer people in the plant, the cleaner it is. And the more automation you have, the fewer people you need.”

That’s not to say that Ivy likes the idea of replacing people with technology, but the fact of the matter is, the industry is facing a skills crisis and automation will help bridge the gap. For its part, however, the OEM is focused on building its team.

Tapping into local resources to build talent

Drake has invested in different workforce development initiatives to ensure they can keep up with increasing customer demands, as well as replace the aging baby boomer generation.

Luckily for Drake, the state of Virginia puts an emphasis on technical skill training, and offers multiple programs to support local manufacturers.

“The state offers a lot of grants at the local community colleges and technical programs where there might be a gap because so many young adults have been pushed toward attending a four year college,” says Robyn Dean, Drake’s controller. “Virginia’s workforce development initiative starts at the high school level and it also happens in technical schools, junior colleges and even the rehabilitation centers for people with disabilities, which really helps us.”

Drake has also participated in the Virginia Department of Labor and Industry apprenticeship for the past 30 years where the OEM provides on-the-job training for incoming engineers and veterans. With a 70 percent success rate, Drake turns out more complete apprenticeships than any other business in the area, according to Robert Bamburg, Drake’s plant manager

“We want to see these apprentices through to completion, and some of them actually end up working for our company in the end,” Bamburg says. “We also do a re-training program here. There was a company close by that was shut down, and we got a couple of employees from them. We were paid by the state of Virginia to re-train them, and in return, we gave them a skill so that they were prepared to go back out into the workforce.”

But the OEM doesn’t just focus on acquiring or training workers in the technical part of the business. Drake also takes on interns at both the college and high school level in its human resources and marketing parts of the business, too.

“We do not limit or focus our intern program to one part of the business because in the end, it helps us grow talent. And it gives students a realistic review of what they’re in for, and what the real world is like,” Dean says. “And I think another great thing about our internship program is that we have to teach our process to each new intern, and it makes you think about that process. If you can’t explain it or teach it, there’s probably a problem with it. So it improves you as an organization.”

Aside from internships, Drake also provides equipment and tours to local schools to build a relationship that is mutually beneficial.