As a well-established milk producer in both fresh and ESL formats, Byrne Dairy probably didn’t need to branch out and build a brand new plant for the purpose of making Greek yoghurt and sour cream. But the fact that the Syracuse, NY-based firm elected to do just that speaks volumes about who the company is and how it views its future.

“We’re big believers in innovation,” says Senior VP and Chief Operating Officer Nick Marsella. “That’s why this plant is here. We’re an 83-year-old family-owned company with the third generation at the helm, and leadership is looking to the future and to where we need to be in the next generation. With fresh milk sales off 2% a year lately, you won’t see us investing in new fresh milk lines right now. But putting $45 million into this cultured products plant and investing another $45 million next year at our ESL plant, those are the investments that represent the future of the organization.”

Located in the Finger Lakes region of upstate New York in the town of Cortland, the new plant occupies 75,000 sq ft. Some 55,000 sq ft are pretty well occupied with producing and packaging yoghurt and sour cream. The other 20,000 are for activities that may not come to fruition for at least another two years: 10,000 sq ft for an artisan cheese operation and 10,000 sq ft for agritourism activities (see pwgo.to/1709).

When plans for the Cortland plant were first drawn up, it was to be for the production of Greek yoghurt alone. “But the past few years have seen a lot of capacity coming on in that category,” says Marsella. “So we decided to put conventional yoghurt and sour cream in the mix here, too. It’s a reminder of how helpful it is to set up these new plants to be flexible.”

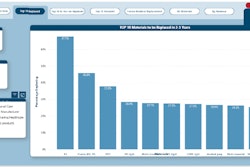

Now running in the plant are five lines, each characterized by its filler:

• A high-speed line with a linear in-line filler from Osgood (www.osgoodinc.com) that does single-serve cups at 420/min

• A four-up rotary filler from Osgood that does 35 cycles/min and fills multi-serve containers with as much as 24 oz of product

• A one-up rotary filler from Osgood for 5- and 10-lb containers

• A one-up filler from T. D. Sawvel Co. (www.tdsawvel.com) for 20- and 35-lb pails of yoghurt or sour cream

• A tote line for 2,000-lb portions of product shipped to institutional customers

HEPA-filtered room

Our focus here is on the high-speed linear line and one of the two rotary lines. Both are in a HEPA-filtered room that is separated from the room in which secondary packaging is done.

“We learned a lot from our ESL plant,” says Marsella when asked why the filling room is HEPA-filtered. “Like how to move people through a manufacturing operation in a way that doesn’t jeopardize air filtration, for example. So we wanted to put some of those lessons to work for us here in the yoghurt plant.”

Sanitation and shelf life considerations also helped the firm pick Osgood as the supplier of its filling systems. “We knew Osgood had a linear machine that included hydrogen peroxide and UV light sterilization, so installing that system was relatively straightforward. But at the time they had no rotary system with UV and peroxide, so the two rotary systems we have here are Osgood’s very first. We wanted to get the extra week’s shelf life and still keep our ingredient statement clean by eliminating additives and preservatives in most of our products.”

The linear filler for single-serve cups is designed for a maximum throughput of around 420 cups/min, though Byrne runs closer to 360. Cups are denested into carrier plates that hold 12 cups across the machine direction.

This is an UltraClean filler for producing Extended Shelf Life packages that are stored, shipped, and merchandised under refrigerated conditions. Shelf life is 70 days.

Polypropylene containers, which come from several suppliers, may have graphics printed directly on the sidewalls, may have in-mold labels, or may have paper or film labels applied to the sidewalls. Regardless of how they are decorated, they are introduced to the Osgood UltraClean filler through a denesting station. From then until lids are applied, everything takes place within the confines of a sterile air chamber.

Just ahead of the sterile air chamber, a bank of sensors from Sick check to make sure that each cavity in the row has a cup. Once inside the sterile air chamber, cups are flooded with hot sterile air. In the next station, cups are injected with gaseous phase hydrogen peroxide that kills mold or bacteria. One advantage of using gaseous phase hydrogen peroxide rather than a liquid spray is that the gas penetrates into all nooks and crannies of the containers more reliably than if liquid is used. Next is another burst of hot sterile air to evacuate the hydrogen peroxide, followed by a station for filling of fruit and then a station for depositing the yoghurt or sour cream.

Sterilization

Now comes sterilization of the pre-cut foil lids with UV light, followed by a heat-seal station that marries the lids to the cups. The final station in the machine is for leak detection. A heated tool comes down on each cup to heat up the headspace inside, which causes the foil-based flexible lidding material to deflect upward. “We look for that deflection with a sensor, and if there is no deflection, we assume it’s because there is an imperfect seal,” says Osgood’s Jonathan Viens. Cups having faulty seals are rejected automatically.

Upon exiting the sterile chamber, cups pass through a Videojet ink-jet system that traverses across all 12 cups to imprint each with date code information. “This traversing system has print heads on top and bottom, so coding can be printed on the top, on the bottom, or on both top and bottom, whatever the customer prefers,” says Marsella. Cups then are lifted up out of their pockets 36 at a time so that an overhead pick head can use its vacuum cups to pick 36 cups at a time and place them in six lanes leading out of the filling room to the adjacent secondary packaging room and an Axiom wraparound case packer from Douglas Machine. It picks a corrugated blank and partially folds leading and trailing flaps as it moves the blank into the station where cups will be loaded. Case loading is done two cases at a time, as two pick-and-place heads pick 12 cups each from infeed lanes and place them on the two case blanks. The Axiom then moves the case forward through folding and gluing stations until the wraparound process is complete.

As cases leave the Axiom system, they are conveyed through an X-ray inspection system from Loma Systems that looks for any case having an incorrect cup count or having a cup that contains a foreign object. Case coding is then done on a Markem-Imaje system before operators palletize the cases by hand.

“Space for automated robotic palletizing was designed in,” says Marsella. “But those systems won’t go in until volumes build to sufficient levels.”

The rotary systems

While the linear system is classified as UltraClean, Osgood refers to the two rotary systems as UltraClean-Light. The difference is that while the linear system has a sterile chamber for sanitizing/filling/lidding, that chamber on the two rotary systems is HEPA filtered, not sterile.

The two rotary fillers are significant because they are the first from Osgood in the UltraClean category. “We’ve made rotary fillers for 40 years, but these are the first that are UltraClean,” says Osgood’s Jonathan Viens. “Byrne Dairy was settled on installing our linear UltraClean cup filler, and once that decision was made they asked if we could also supply rotary systems that were UltraClean. Otherwise they would have had to look to a European supplier. So we agreed to do it.”

Operating on an intermittent-motion basis, the four-up Osgood rotary machine takes cups through pretty much the same routine as the inline system described above—except it does it four-up and in a rotary fashion.

Finished containers are discharged onto a takeaway conveyor that takes them past an ink-jet coder from Videojet. Once it has imprinted date and lot code information on the lid, the cups proceed out of the filling room and into a TriVex top-load case packer from Douglas Machine. On the day of PW’s visit, it was two-lb containers that were being filled, so the TriVex collated them into the pick station two across and six in the machine direction. Then a dual pick-and-place arm picks six cups on one side and six on the other and gently places them in two waiting RSC corrugated cases.

“We try to buy U.S.-made equipment when we can,” says Marsella when aked why secondary equipment on both lines comes from Douglas. “More important, we felt Douglas was a good piece of equipment with good service behind it. Sometimes, because so much of our business is private label manufacturing, our hands are tied when it comes to machinery selection. When customers want something, it always seems like they want it overnight. Sometimes that dictates whose equipment we buy. But in this case Douglas was well positioned to meet our requirements.”

As for Osgood, Marsella says their willingness to develop rotary-style equipment to meet Byrne Dairy’s requirements went a long way. He notes that right around the time these new lines were being developed and installed, Osgood was acquired by Bosch Packaging Technology. The acquisition that was perfectly fine in Marsella’s book. “They’re both fine companies,” he says.

Greek yoghurt growing fast

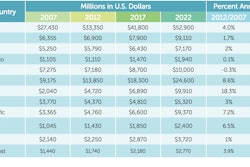

Even though the yoghurt category is experiencing mild growth in the U.S., Greek yoghurt is enjoying explosive growth, accounting for about one-third of the yoghurt consumed. Americans on average consume 12 lb of yoghurt a year, which is half as much as Canadians but one third the amount of Europeans.

Source: PMMI Dairy Industry—a Market Assessment 2013, www.pmmi.org/research