Machine builders and their end-user customers are exposed to sometimes wildly different pressures, but still usually come together in a manner that’s mutually beneficial.

Brand owners are under the gun for fast product launches while SKUs proliferate, and McCormick & Company’s Michael Okoroafor says being first to market can be a make or break proposition for a CPG.

Meanwhile, OEMs are caught between a rock and a hard place with payment terms, as they are expected to pay back controls component suppliers more quickly than big-budget end users often are able to dictate for their own remittance.

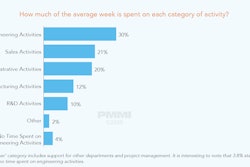

With these potential stumbling blocks and pain points in mind, PP-OEM and Packaging World teamed up to conduct a survey of their respective audiences. The idea was first to map out many of the key interaction points between machine buyer (Packaging World’s audience) and machine seller (PP-OEM’s audience), and then identify areas of noticeable friction.

On many of these topics, builders and buyers seemed to be in agreement, by and large. But that’s not the case across the board. The survey brought into focus several important gaps that separate the two camps. Buyers have pain points they’d like to articulate if given an opportunity. And builders have their own ideas about ways in which the gaps between the two might be better bridged, if only they had the chance.

Seeing eye to eye on FATs

Factory Acceptance Tests (FATs) have a lot of moving parts. So we asked our two audiences which of the many variables involved are the most critical to a successful, or at least representative, FAT. OEMs were twice as likely to say that the availability of the product being packaged in sufficient quantities is critical to a representative FAT. Also, OEMs are also almost 20 percent more likely to say that the product itself being accurately represented is critical to FAT success.

This reflects a common point of contention between OEMs and their customers, in that FATs are often conducted using (and then re-using) small quantities of the product being packaged. This means that products are run through a machine multiple times, and are thus exposed to potential damage several times over. Because of the small quantities and the re-use, those products may not be representative of the pristine products that would come off a production line.

“This is an issue on many of our projects,” says Jeff Bigger, president and CEO, Massman Automation, Villard, Minn. “Unless the product takes up a significant amount of space, we always seem to want more than the customer wants to send. Many times we struggle to execute a good representative FAT due to a lack of quality test material. Not to mention, if you have to pack and unpack, then you’re adding cost to the FAT. I also think it depends on the type of product. If it’s a rigid bottle or can, typically that’s not as big a deal, but when you get into pouches, cartons, and things that can be damaged, then they’re no longer representative of the virgin product the second or third time through.”

Barry Heiser, president, Global Filler & Integrated Solutions, Pro Mach, Cincinnati, says the very act of shipping from the production plant to the location of the FAT can change the products’ properties. So, the products going into an FAT aren’t the same as the product coming off of a production line.

“And then, if you have to reuse the stuff over and over again, you’re chasing your own tail because it becomes totally different after going through the machine once and that’s not real world because you’re only going to pack it once,” he adds.

Frozen products present a special challenge. Coming off the line, it may not even be frozen, but it could be the type of item that needs to be frozen in order to be sent to the OEM for the FAT. In those conditions, it’s impossible to simulate what you see in the production plant.

John Giles, manager, Operations Engineering, Amway, Ada, Mich., is sympathetic with these observations. But he points out that CPGs have their own set of issues and pressures to deal with.

“Ideally, we would like to send more products. There’s always that cost factor, and then is the product even available? In particular, if we’re launching a new product and we may not have all the packaging available, that’s where we run into that situation where we have limited samples, or they’re pre-production components,” he says. “Then, we’re trying to run those pre-production components through the FAT, waiting on the real components to arrive. We’re under a time crunch and just trying to get the equipment accepted and installed in time for those new components to come in. Our best supplier partners understand that and work with us.”

Mark Green, manager, Global Engineering, Abbott Nutrition, Columbus, Ohio, agrees, and says it goes beyond the components. Even when they have the correct corrugated or paperboard material for carton or case, it is likely to have come from some type of mock-up machine. So even though the materials are correct, the quality of those materials may not be representative of what would be expected of the final production material.

In fact, many times the containers that end users are packaging in a FAT might even be expensive-to-make SLAs (stereolithography, or 3D-printed prototypes). Beyond the expense, an end user would have limited quantities of them because so much is being done in parallel. Speed to market is always tops in the end user’s mind. In these cases, OEM’s firmly state that they cannot begin to simulate factory conditions.

“When they come up with a new, say, bottle, they do one-off molds and they get enough samples to do the market test. They get enough samples possibly to do the run-offs, but then when it goes to production molds, they’re different,” Heiser says.

Further complicating the FAT, any issue is magnified at speed according to Heiser. At slower speeds, there’s room for leeway, but for faster speeds—which tend to correlate with larger, more sophisticated end users who expect the FAT to perfectly reflect production conditions—any little issue can throw off the entire FAT.

Scott Reed, VP, Sales, Marketing & Customer Service, ADCO, Sanger, Calif., says that having experienced parties on either end tends to lead to common ground.

“There’s an education component that goes along with it, which takes time, energy, and effort,” he says. “And a lot of times it’s a tough sell. You find yourself trying to rationalize with certain individuals about why you need so much product, and getting their buy-in can be very difficult. You find this less with people who have been through the process before. They generally understand. At the end of the day, the smaller companies tend not to want to waste as much product or use as much product because they’re budgeting every penny.”

In Giles experience, it comes down to the communication between the OEM and the end user. He thinks there has to be a balance between what is sufficient to send and what the OEM asks to be sent.

“It’s up to the OEM to say, ‘Hey, I have to have this minimum quantity, and here’s the reasons why,’” Giles says. “And obviously, the end user has to try to come up with that, but we may challenge the OEM and it has to be a discussion. We might say, ‘OK, look, here’s our situation, here’s what we’re going through, and here’s the number I can get you.’”

Giles cites several different scenarios in which he and the OEM were able to make it work with limited quantities, knowing they’d have to recycle a bunch of product components through multiple times.

“Then, they’d typically set aside the test components and say, ‘In the midst of all the re-run components, we’re going to mark and send through our sample units so we can pull those and use those for our auditing purposes.’ We’d make sure that they weren’t getting scuffed, that they’re not damaged, torqued, or cracked,” he says.

Green agrees, and feels that unfortunately, the end users’ hands are tied, and only so many products will be available. But he recognizes that this just increases the risk that when the CPGs get the machines into their facilities, on site failures may result because the materials used for the FAT and all the development work were re-used so frequently.

“We’ve had some major line-feed jamming issues because the containers themselves were pressed against each other so tight, they wouldn’t release. We had logjams at the spots where the conveyors narrowed because of the dynamics of that virgin bottle versus the re-used bottle. So we know that they do not function the same when they’re re-used as they do when it’s their first time through the machine,” he says. “If the OEMs recognize that we have limited quantities, we recognize that the FAT can’t be perfectly representative, and can communicate that to our people. We all recognize that it’s a thorny issue with no easy answer.”

In a less pronounced trend we noticed in the survey results, end users are more likely to point to accurate representation of length and speed of test run as being critical to an FAT. They are also more likely to cite upstream and downstream equipment, which OEMs aren’t likely to be able to replicate, as important to an FAT.

Of note, the Capital Projects Solutions Group within the OpX Leadership Network, convened by PMMI, published an FAT checklist (available here) that stands to smooth some of the rough edges that FATs can present between end user and machine builder.

Reasons for selecting controls components

Another gap between end users and their OEM suppliers is evident in how controls components are selected. We see that OEMs are twice as likely to look for best in breed controls components, while end users are twice as likely to look for easily service/replaced controls components.

End users Green and Giles described their rationale for erring toward easier service and replacement over the best in breed.

“We try to stay consistent in our controls components for a couple of reasons. The internal service element is one,” Green says. “Our own controls engineers and electrical maintenance folks are familiar with a certain platform, so we try to standardize on keeping that the same. Then, of course, the availability of external service as well matters quite a bit to us.”

Giles agrees that this is a major issue for him as well, and says that most of the time, the latest and greatest controls or features that the OEM may be proposing are “too far out there for our purposes.” Amway’s operators and personnel benefit from the element of commonality and ease of use.

“When we talk about platforms,” Giles says, “there’s the platform that interfaces with the operators, and then there’s the platform that runs in the background. There have been cases where the OEM has stated that if they’re forced to use the same platform for the operator interfaces that they’re using for the behind the scenes control of the machine, it will dumb the machine down and slow response time. On a case-by-case basis, we have allowed them to do that, as long as there’s a rationale there. But carte blanche, we’re not going to say do it without asking us because we want to make sure we agree with their logic.”

Reed says that OEMs in general have to be responsive to an end user’s familiarity requirement. His own company, ADCO, tends to stay with more traditional or established solutions as a result of the pull-through demand. Naturally CPGs want to go with what’s familiar, what’s easily serviced, and what’s readily available. After all, end users have MRO inventory, and they have installed base of controls components already.

“That said, I think there’s certainly some opportunity for innovation that’s being slowed up by adherence to the tried and true. I think it’s fair to say that when we look at new competing technologies, there are some interesting things out there, but OEMs may tend not to apply them only because of fear, uncertainty, and doubt of acceptance,” he says.

Reed, Bigger, and Heiser agree there’s some change in the air on this, though. Reed is even starting to see more customers approach him about alternative controls.

“I think the work some of the smaller controls component suppliers in the marketplace have done, is starting to resonate. Comments from the alternate vendors used to be, ‘Oh yeah, they accept our platform too,’ but now we’re actually hearing it from customers. It makes the challenge for us a bit easier. We’re starting to see some shift in the marketplace in terms of pull-through opportunities.”

Bigger adds that the increase in foreign, international equipment among North American packagers is accelerating this mood shift.

Also, Rockwell Automation, which has long enjoyed de facto standard status among North American packaging machinery manufacturers, is currently launching an entirely new product line in the packaging machinery market segment for motion control, I/O, and more.

“As the current Rockwell platforms go silver and new ones are introduced the playing field for inventory will begin to level,” Heiser says. “But it will also give us new technology opportunities in the Rockwell platform.”

PackML pull not yet matching push

The survey revealed a familiarity gap between OEMs and their end user customers with regards to PackML. Almost 60 percent of OEMs are at least aware of PackML. On the end user side, only a bit more than 40 percent are familiar with PackML.

These survey results seem to substantiate Reed’s sense that while PackML has been pushed for some time throughout the world of automation, the end user has yet to ask for it frequently enough to create a corresponding pull. He says ADCO specifies PackML with or without the customer request, because from a competitive standpoint, not doing so could be a negative differentiator. “Even though the market isn’t necessarily asking for it now, we look at it as a potential competitive leveler,” he says.

And for those end users that are interested in implementing PackML, cost can be a hurdle. “Everybody wants it, nobody wants to pay for it,” Green says. And Heiser has had the same experience in dealing with CPGs.

“It’s interesting when a CPG buys multiple machines in line, and because Pro Mach uses PackML as a standard, we explain that the programming architecture is the same whether it’s a sleever or a case packer, and when you go to the HMI, all the screen navigations look the same,” Heiser says. “If they’ve never heard of it, they tend to love the idea, but immediately ask if they are going to have to pay for it. If we say ‘no,’ then they continue to like it.”

“If it’s there,” Giles says, “it just makes the integration of the systems easier for us as an end user. The problem we’ve run into is when we want to see it implemented, then the OEM wants to charge us for the development of it.”

This is a sore spot for Giles and end users in general. They often feel they are paying for development of a new custom technology or capability, in this case PackML, that the OEM will then be able to add to its standard offering at a standard price. So Giles doesn’t want to pay a premium for custom development of something that his competitors will be able to get off the shelf from the same OEM.

Green adds that while PackML had become a new standard for Abbott and is onboard any new lines they might buy, adoption is much slower in replacing components of older or existing lines.

“Consider bringing just one new machine in to replace an existing component on a line,” Green says. “Suppose I’m replacing a labeler. If it comes standard with PackML, but the rest of the line isn’t PackML-ready, then I’m not going to pay the extra money to convert the rest of the line over to PackML. Can you then say that a line that’s using that new labeler with PackML is up and running with PackML? I would say no.”

Lead time top pain point for OEMs, end users alike

Throughout the survey, we found many areas of strong commonality between OEMs and end users. Lead time as a major pain point is one example, as nearly half of both audiences reported that the pain of condensed lead times is one of their top three difficulties among 11 potential pain points we asked about. Builders and buyers alike also frequently reported difficulty with design changes after a signed PO (27 percent and 30 percent respectively). Builders and buyers even agreed that TCO, at least compared to the other issues presented, wasn’t much of a pain point (13 percent and 12 percent respectively).

But outside of lead time, design changes, and TCO, OEMs and end users reported differing sets of hardships. Machine builder problems were much more likely to reflect disagreements over price (41 percent compared to 26 percent) and payment terms (26 percent compared to 13 percent). Payment terms continue to be a tough issue, particularly for OEMs, as about a third of end user respondents actually report that net 90 or longer payment terms constitute fair repayment.

End users interviewed for this story were actually surprised by the leniency of OEM responses.

“To me, the surprise is that 42 percent of OEMs said net 60 is okay. We went to a net 60 model about 2 years ago, and it was a disaster as far as the OEMs were concerned. It ends up being a procurement and negotiation thing for us,” Giles says. “But we take the first stab at that net 60 days and we’re responsible for that. If the OEM doesn’t deem that acceptable, then we let them deal with our procurement department. We get out of it at that point.”

Meanwhile, end users were far more likely to cite as a pain point disagreements over what constitutes realistic OEE (37 percent compared to 12 percent, or three times more likely to find it a pain point), disagreements over after sales service (21 percent compared to six percent, or more than three times more likely to find it a pain point), and disagreement over proprietary engineering (15 percent compared to six percent, or almost three times more likely to find it a pain point).

In particual, the aforemention OpX Leadership Network has created tools to get both parties on the same page on to both TCO and OEE. The OEE Benefits Calculator is available here, and the TCO Playbook and Checklist are available here.

Green also points to the disagreement between OEMs and end users on how long it takes to get a line or machine commercially up and running. “That’s a big part of how OEE is calculated, so really, it’s a subset of the OEE disagreement,” he says. “Both are a big problem for us as end users.”

Green says Abbott will typically put an OEE threshold in the contract as a key performance indicator. But each individual OEM that contributes to a line will say that its machine can’t be judged in a vacuum, as it’s subject to the OEE of upstream and down stream equipment. They claim end users are then holding OEMs accountable for things that are out of their control.

“But it’s a whole system,” Green says. “So in looking at this as a responsible manager, I’ve got to say, ‘It doesn’t matter if one element of this line isn’t running up to par, my whole line OEE is down. It’s all got to work together.’”

Amway uses a similar approach, and Giles also struggles with getting every OEM on the line onto the same page, and understanding what that OEE means.

“Again, OEE requirements can change based on new information, but it has to really be discussed early on between the OEMs, communicating what the end users’ situation is, and how we’re installed on the line. Are you going to apply the other pieces of equipment to that OEE number, or are you just going to treat it as a standalone? Getting everyone, OEMs and us as end users, onto the same page on all of these pain points is the real challenge,” Giles says.

How do pain points differ between OEMs and end users?

This set of responses represents a comparison between what OEMs and end users consider to be their top pain points in the buying process. Larger gaps between the two answer sets indicate mire disparate answers. Responses add up to more than 100 percent because each respondent was able to choose as many as three answers. The question was worded as follows: “Which [of the above possible responses] are the biggest stumbling blocks along the path from buying, to building, to installing machinery.” The term “Disagreement” was specified in respective surveys to read “Disagreements with End Users” on the OEM survey, and “with OEMs” on the end user survey.

Methodology: This set of responses represents a comparison between what OEMs and end users consider to be their top pain points in the buying process. Larger gaps between the two answer sets indicate mire disparate answers. Responses add up to more than 100 percent because each respondent was able to choose as many as three answers. The question was worded as follows: “Which [of the above possible responses] are the biggest stumbling blocks along the path from buying, to building, to installing machinery.” The term “Disagreement” was specified in respective surveys to read “Disagreements with End Users” on the OEM survey, and “with OEMs” on the end user survey.